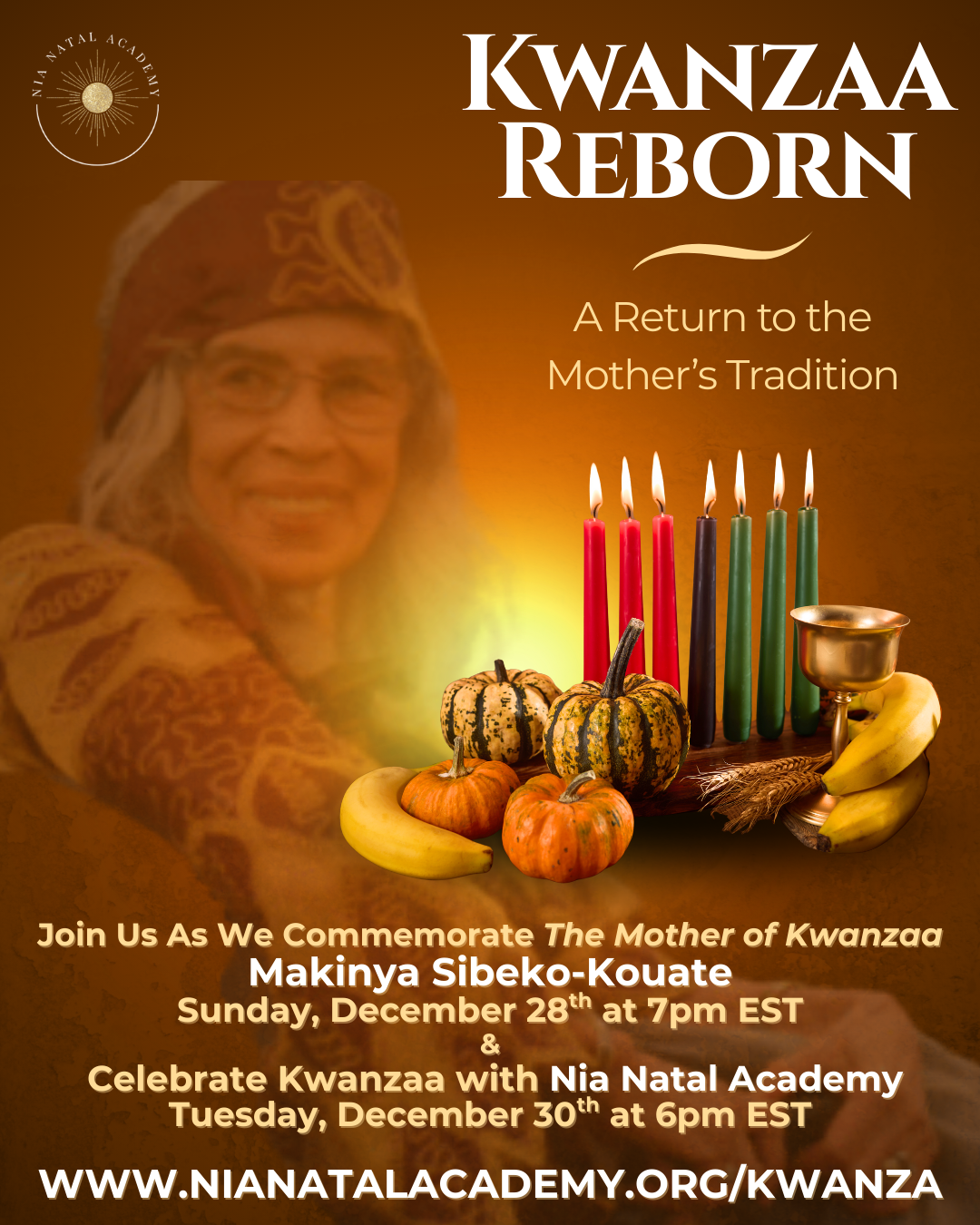

Telling the Whole Story

Mother Makinya Sibeko-Kouate and the Work Behind Kwanzaa

Before we talk about Kwanzaa, we must talk about the woman.

Before the principles were widely printed, before books and stages and annual programming, there was Makinya Sibeko-Kouate. She was born Harriet Smith on July 1, 1926, in San Leandro, California, raised in South Berkeley, and shaped by a lineage of Black organizers, educators, and freedom fighters who understood that culture is not inherited automatically. It is taught.

Our students began their research with her life, and what they found was not a footnote, but a foundation.

Mother Makinya grew up in a family where education, discipline, and service were non-negotiable. Her mother, Willette Smith, was deeply involved in African American social and fraternal organizations. Her ancestors were tied to early Black labor movements, the Colored Conventions, and Black mutual aid societies long before the mid-20th century. By the time Mother Makinya was a child, she was already being raised inside a living tradition of responsibility to community.

She graduated from Berkeley High School in 1947. As a teenager, she studied piano and taught other children music by the age of thirteen. During World War II, she became the first Black woman air traffic controller in Alameda, guiding planes safely to the runway, which was work that required precision, confidence, and calm under pressure. These were not minor accomplishments; they were early indications of the kind of leader she would become.

In the early 1950s, she studied music and teaching at San Francisco State College, later attending San Francisco Teachers Normal College. From 1965 to 1968, she attended Merritt College in Oakland, where her leadership would leave an indelible mark. There, she was elected the first Black student body president in the Peralta Community College district, and she played a central role in the development of one of the earliest Black Studies departments in the country. Education, for Mother Makinya, was never neutral. It was a tool for liberation.

Our students traced her work across multiple roles as educator, organizer, mentor, cultural worker, real estate manager, potter, journalist, and radio host. They documented her leadership within the National Black Student Union, her facilitation of education workshops at the National Black Power Conference in Philadelphia in 1968, and her activism against police brutality, including incidents where she and her mother were assaulted by police in their own home. This was a woman who did not theorize freedom from a distance. She lived inside the struggle.

It was from this grounding — education, organizing, woman-led community work — that Kwanzaa emerged as a practice, not an idea.

Our students learned that while concepts for a new Black holiday circulated in the mid-1960s, it was Mother Makinya who translated theory into lived tradition. In December 1967, she hosted one of the first documented seven-day Kwanzaa celebrations in her Berkeley home. These were not symbolic gatherings. They were structured, intentional, family-centered observances rooted in African harvest traditions and guided by the Nguzo Saba as daily principles.

In 1969, she authored a mimeographed document titled Kwanza, now recognized by libraries and rare-book institutions as the earliest detailed instructional guide defining the holiday; its symbols, meanings, dates, and procedures. Her personal archive includes Swahili vocabulary cards, lesson materials, and documentation from her study of African harvest festivals. She did not merely repeat language; she built curriculum.

Most importantly, she taught. She traveled across dozens of U.S. states, throughout Africa, and internationally, training families and communities in how to practice Kwanzaa, not just perform it once a year. She mentored women, organized community committees, and ensured that children were always included. Our students came to understand that this is how traditions survive: through mothers who teach, correct, and carry.

It was at this point in their research that we turned to an additional primary source: Mama Ikenna, who served not to introduce a new story, but to confirm what the children were already uncovering.

When Mama Ikenna joined our class, she did so as an elder, a cultural worker, and a protégé of Mother Makinya. Our homescholars prepared their questions carefully, understanding that oral history is not casual conversation, but a sacred responsibility.

As she spoke, the written record came alive.

Mama Ikenna described Mother Makinya as statuesque, brilliant, fearless, and deeply joyful. She emphasized that Mother Makinya was especially devoted to children, insisting that the Nguzo Saba be taught as a way of life, not a seasonal script.

“She was lively and open with the children,” Mama Ikenna shared. “She wanted them to understand the principles as something you live.”

(Zoom interview, approx. 00:18:40)

When students asked how Kwanzaa spread before books and media, Mama Ikenna explained that it moved the way culture has always moved; through women, through homes, through word of mouth.

“It spread through people,” she said. “Through women. Through homes.”

(Zoom interview, approx. 00:27:10)

She spoke about Sisters of Tomorrow, an organization Mother Makinya helped establish and nurture, where girls were mentored and cultural practice was treated as life skill. She described Mother Makinya’s approach to libation ceremonies, insisting that elders, parents, and children all be named so no generation was left out.

“She always made sure the children were included,” Mama Ikenna told us. “Because if they don’t know, the tradition doesn’t last.”

(Zoom interview, approx. 00:34:55)

For our students, this was the moment the picture fully assembled. The documents. The timelines. The archive. The elder testimony. All of it pointed in the same direction.

Mother Makinya Sibeko-Kouate did not simply assist with Kwanzaa.

She developed it, structured it, taught it, and carried it.

She mothered the holiday into existence as a living, seven-day, family-centered, African-rooted tradition. She wrote the earliest known instructional materials. She organized the first sustained celebrations. She trained the people who would carry it forward. And she did so without chasing recognition; focused instead on whether the work would survive intact.

This is why, at Nia Natal Academy, we reverence Mother Makinya as the true creator and developer of Kwanzaa as it is practiced.

Not only because others were absent, but because her labor made the tradition real.

We share this work publicly because our students deserve to see their scholarship honored, and because our communities deserve a fuller, truer story. This article is part of an ongoing archive. We will continue to add transcript excerpts, visual documentation, and additional primary sources as they are reviewed.

This is how culture is protected.

By listening. By documenting. By teaching our children to return to the source.

Witness Our HomeSCHOLARS interview below.

The interview begins at the 28 minute mark.

Our Sources & Archiv

Timeline: Sister Makinya’s Work vs. Karenga’s Publications

1965–66 – Student leadership and Black Studies

Harriet Smith (later Sister Makinya Sibeko-Kouate) attends Merritt College in Oakland, becomes the first Black student body president in the Peralta district and helps develop one of the first Black Studies departments. blackbirdpressnews.blogspot.com+1

Dec 1966 – Karenga’s idea meets her organizing power

As student body president, she and other students attend a Black student conference at UCLA, where Maulana Karenga hands her a mimeographed sheet with ideas for a new Black holiday called “Kwanza.” blackbirdpressnews.blogspot.com+1

Dec 1967 – She establishes Kwanzaa as an actual seven-day ceremony

Back in Oakland/Berkeley, Sister Makinya hosts one of the first Bay Area Kwanzaa celebrations in her home and organizes a full seven-day ritual observance.

Community tributes describe her as “responsible for the establishment of Kwanzaa as a seven day ritual ceremony for African people beginning in December 1967.” blackbirdpressnews.blogspot.com+2New Afrika History+2

1969 – Her written Kwanzaa guidelines (earliest known defining document)

A rare 1969 two-page mimeographed document titled “Kwanza” by Harriet Smith lays out the meaning, symbols, dates and procedures for the week-long celebration.

A rare-books description notes that she “drafted more elaborate and specific guidelines for the holiday” and calls it “the earliest document defining Kwanzaa recorded at any institution in the United States, as per OCLC WorldCat.” Max Rambod

Late 1960s–1970s – She spreads the practice across the world

She travels to 36 U.S. states, 13 African nations, Europe and Mexico teaching Kwanzaa/Nguzo Saba and organizing community celebrations. Jpanafrican+2New Afrika History+2

Bay Area organizers recall that she and others produced the San Francisco Bay Area Kwanzaa Committee’s first Kwanzaa/Nguzo Saba handbook and led the inaugural 1967 community celebrations. New Afrika History+1

1972–1977 – Karenga’s first major publications appear

Haki Madhubuti publishes Kwanzaa: A Progressive and Uplifting African American Holiday in 1972, reflecting that Kwanzaa is already a practiced tradition by then. Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia

Maulana Karenga’s first extended book solely on the holiday, Kwanzaa: Origin, Concepts, Practice, is published in 1977 by Kawaida Publications. Equip+1

Later, he publishes Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community & Culture in the late 1980s/1990s. Wikipedia+1

So in terms of documented paper trail available to the public:

Her detailed written guidelines (1969) and her role in organizing seven-day Kwanzaa rituals are on record years before his widely circulated explanatory book (1977). Max Rambod+2Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia+2

The only clearly described 1960s defining Kwanzaa document that institutions and rare-book dealers currently point to is hers. Max Rambod+1

That doesn’t mean he never wrote anything in the 60s; it does mean that what the public and archives can point to as full, early written instructions comes with her name on it, not his.

“Let the People Tell It”: Voices Calling Her Mother / Co-Creator

Community historians & activists

A New Afrikan history blog honoring her states that “Queen Mother Makinya is responsible for the establishment of Kwanzaa as a seven day ritual ceremony for African people beginning in December 1967.” New Afrika History

The same piece insists: “It was a New Afrikan Black Woman who was and is the co-creator of Kwanzaa… it’s time she get her credit!!!” New Afrika History

The writer describes his own experience: he thanks “Sister Makinya Sibeko-Kouate (who my heart and soul know as the Mother of Kwanzaa)” and credits her, Fred T. Smith, and ASET Sister Barbara Duggan with producing the first Bay Area Kwanzaa/Nguzo Saba handbook and leading the inaugural 1967 celebrations. New Afrika History

Bay Area Black arts & journalism

Journalist Wanda Sabir writes that “Sister Makinya is responsible for the establishment of Kwanzaa as a seven-day ritual ceremony for African people beginning in December 1967.” blackbirdpressnews.blogspot.com+1

She recounts that Karenga gave Makinya “a mimeographed sheet of paper with ideas on a new Black holiday called Kwanza” and that after returning to Oakland, Makinya hosted one of the first Bay Area Kwanzaa celebrations in her home and then took Kwanzaa around the world. blackbirdpressnews.blogspot.com+2New Afrika History+2

Community organizations and Pan-African spaces

Multiple tributes and event descriptions refer to her as “Queen Mother of Kwanzaa” and “Mother of Kwanzaa,” crediting her with bringing the first Bay Area celebrations and spreading the holiday to dozens of states and multiple countries. facebook.com+3Pinterest+3Visions & Victories+3

Together, these voices are saying what you are saying:

She didn’t just “promote” Kwanzaa. She established the ceremony, wrote the early guidelines, and mothered the living practice.

Where People Can Actually Find Her Original Documents

1. Sister Makinya Sibeko-Kouate Papers – Bancroft Library (UC Berkeley)

Collection title: “Sister Makinya Sibeko-Kouate papers, BANC MSS 2019/135” OAC

Held at: The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

The finding aid notes that she was “celebrated for her efforts to promote Black Studies curricula in the East Bay and to popularize Kwanzaa” and that her papers contain flyers, notes, and materials showing her efforts to define and promote the holiday. UC Berkeley Library Update+1

People can search online for “Sister Makinya Sibeko-Kouate papers Bancroft” and then contact the library for access.

2. 1969 “Kwanza” mimeograph – earliest detailed definition on record

A rare-books listing describes a 1969 two-page mimeograph titled “Kwanza” by Harriet Smith as “the earliest document defining Kwanzaa recorded at any institution in the United States, as per OCLC WorldCat.” Max Rambod

It states that she “drafted more elaborate and specific guidelines for the holiday” and began a campaign of celebrations and teaching based on that document. Max Rambod

Even though that particular copy is/was in the rare-book market, its description confirms that her written outline is what institutions recognize as the earliest full definition of the holiday, not a 1960s text by Karenga.

3. SF Bay Area Kwanzaa/Nguzo Saba handbook

Community accounts refer to “the San Francisco Bay Area Kwanzaa Committee’s first Kwanzaa/Nguzo Saba handbook” produced by Sister Makinya, Fred T. Smith, ASET Sister Barbara Duggan and others. New Afrika History

Copies of this likely live in her Bancroft papers, in Bay Area community archives, and possibly in private collections of elders who served on those committees.

4. People Connected to Her: Proteges, Comrades, Lineage

She was fourth generation in a pioneering African-American family with ancestors tied to Madagascar, Tanzania, and freed Virginian enslaved people who migrated to California before the Civil War. blackbirdpressnews.blogspot.com+1

A tribute notes she was “the last survivor in her direct family line” and left no biological descendants, but a “multitude of friends, acquaintances and extended family who considered her their beloved and treasured sister.” blackbirdpressnews.blogspot.com

Community remembrance identifies Sis. Ikenna Ubaka as “one of her many proteges,” showing that her legacy continues through students she trained in Kwanzaa/Nguzo Saba practice. New Afrika History

She is repeatedly named “Mother of Kwanzaa” and “Queen Mother of Kwanzaa,” reflecting not just affection but a recognition of her foundational role in establishing and carrying the holiday.Pinterest+2Visions & Victories+2

Authored by Mama Nia Sade & Mama Messina Wattley